In November 2016 – shortly after Donald Trump was elected nearly three years ago – I wrote the following article for The New Statesman about his use of racism as a political strategy in order to appeal to the grievances of white Americans who feel that their sense of identity is under threat.

As I wrote then: “Although using division for votes is nothing new for Republicans, Trump appears to be acting directly from the Southern Strategy playbook – a Nixonian strategy from the Seventies based on the exploitation of racial tensions and divisive politics aimed at increasing discord in order to maintain Republican presence.” (Isn’t it fascinating that Trump has been compared to Nixon in many other ways over these last 3 years…? Perhaps his fate will be the same…)

Trump’s racist/racial/racialized agenda has always been clear to me. Unlike others – such as George Conway, husband of Trump mouthpiece Kellyanne and Trump critic/foe, who just finally concluded this past weekend that Trump is indeed a racist and wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post about his new found discovery – I have not been surprised nor in denial about the depths of his animus towards people of color. Dismayed, often. Saddened at times. But shocked? Absolutely not. I know racism when I see it. My very survival depends on that.

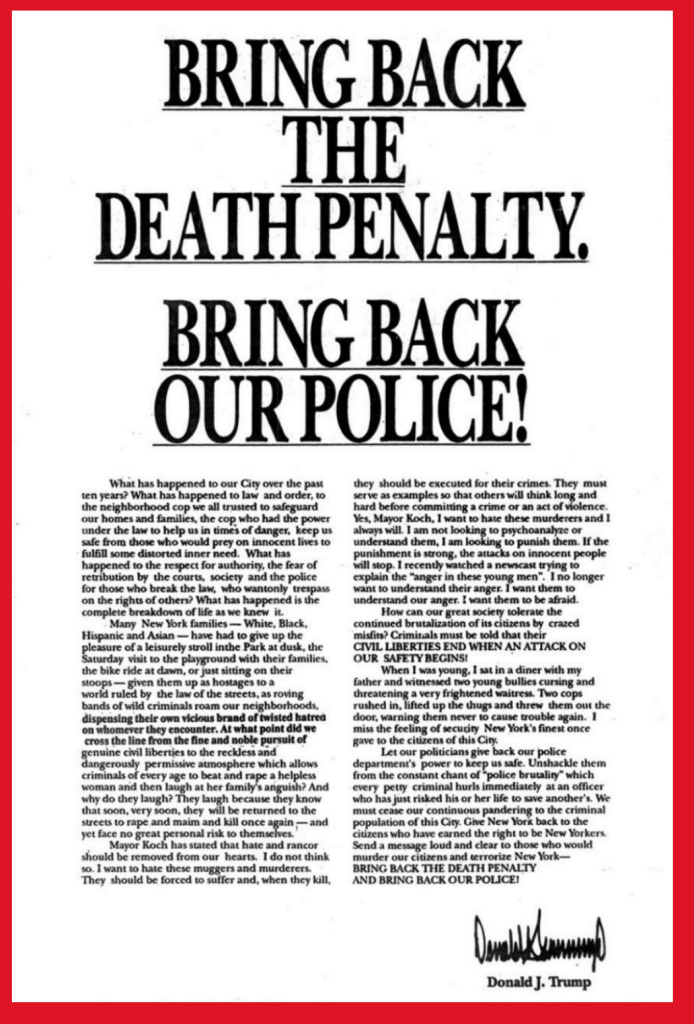

Trump’s racism is long and old, and it certainly has never been hard to miss. If you can’t cast your mind back to 1989 and his front page newspaper adverts calling for the death penalty to be brought back and used in the case of the so-called Central Park Five – the group of 5 young black men who were wrongfully imprisoned and later exonerated for the rape of a female jogger in Central Park – you should at least be able to remember that he actually got President Barack Obama to produce a copy of his actual birth certificate after insisting – in a bizarre conspiracy theory – that there was no way Obama was actually American. Trump has been at this game for quite some time now. And even though he been proven very wrong – as he is on most things – he is good at it.

As the country grapples with Trump’s most recent insults, this time aimed at Reps. Ayana Pressley, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Rashida Tlaib, four freshmen Democratic women of color in Congress (all American, one foreign-born) who he tweeted should “go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came,” I have gone back to review this piece. Not only is it prescient, but it seems to get even more accurate the longer Trump is in office.

The piece was originally titled “Make America White Again: how US racial politics led to the election of Donald Trump”. However, you could title it: “How and why Trump uses racism as a political tool” or “How Trump’s racism works” or “How Trump will use racism as part of his 2020 re-election strategy” and I’m saying the same thing…

Unfortunately, given that Trump sees racism as a tool to be exploited and as a effective strategy to be utilized to appeal to his base, we can only expect more and more of this toxic and hateful rhetoric from Trump and his camp between now and November 3rd, 2020.

When President Barack Obama was elected in 2008 and 2012, there was much talk of the “Obama effect” and what his presidency would mean. In some circles, that talk leaned towards the optimistic, with visions of unity, civil rights advances, and the positive symbolism of his election given America’s history of institutionalised segregation and systematic prejudice.

While many liberals have been critical of Obama’s policies and expressed disappointment about what he has done (or failed to do) in office, one underestimated effect was the other side of that coin: the counter-reaction, the anger, sadness and sense of victimisation that eight years of an African-American president would invoke in some Americans.

Some of that counter-reaction could be put down to party politics. After all, nobody wants to see a rival party stay in power for too long. However, some of that anger was about something much deeper, more sinister and, in truth, more in line with an ugly historical status quo. For some, being president was simply not Obama’s rightful role in the American story; that he ever got to the White House, and for so long, was in itself a cause for concern.

As time went on, I personally noticed a growing sentiment – exploited by right-wing media – that white Americans were losing out under this black president, and that white identity and culture (supposedly the de facto“American way”) were being threatened by this move towards a more open, inclusive and diverse society. That is, America as some people knew it was changing, quickly – and for the worse – as women, minorities, gay people and others were apparently being promoted, affirmed and championed at the expense of white people.

Those who believed that they should exclusively be the political, social and culturally dominant participants in, and holders of, the country’s rights and privileges were increasingly aggrieved by what they perceived as statewide affirmative action that was leaving them out in the cold.

One of the Americans disturbed by Obama’s election was now-President-Elect Donald Trump. His discontent became apparent in 2011 when he emerged as one of the key proponents of people on the extreme right claiming that Obama was not a US citizen and, therefore, did not legitimately hold the rights to the presidency.

Objectively, there was no reason to believe that Obama was not a natural born citizen. Indeed, the real reason for taking this view was to undermine his presidency and to promote the notion that the only way a black American had become president was due to some kind of fraud or conspiracy.

Given that the entirety of this nation’s civil rights activism has been based on the fight for African-Americans, other people of colour and oppressed groups to have full participatory rights and be treated fairly and equally as full American citizens (as opposed to partial ones), the Birther issue had deep racial significance. It spoke to, as well as embraced, a highly racialised worldview. At that point, Trump unequivocally aligned himself with the extreme angle of contemporary American right-wing politics.

In reality, if one looks at Trump’s history, his attitudes and behavior should not that surprising. He has consistently demonstrated that he holds unsavory and prejudiced views of people of color. It is for this reason that his open alignment with people who subscribe to the “alt-right” (a modern euphemism for people with extreme far-right views, including white supremacists) vision of America and his promotion of people like Steve Bannon is not something that should be taken lightly.

What we are witnessing are the early stages of Trump’s campaign pledge to “make America great again”. Something that some – myself included – take as a coded way of saying “make America white again”. Trump’s choice of language during his campaign, and the people he has appointed since being elected, compound this interpretation of a slogan that is becoming ever more frightening.

Although using division for votes is nothing new for Republicans, Trump appears to be acting directly from the Southern Strategy playbook – a Nixonian strategy from the Seventies based on the exploitation of racial tensions and divisive politics aimed at increasing discord in order to maintain Republican presence.

Interestingly, just as Trump’s victory has come off the back of a black president, Black Lives Matter, and more movement towards increasing rights for minorities in America, the Southern Strategy really came into play during and after growing civil rights protests.

As hard as it is to stomach, there are still people who believe in the inferiority of people of colour and women, who believe that segregation and separation was, and is, a good thing, and that white people (men, especially) have a natural right to power – both in the country and in the world.

If indeed Trump is a throwback to Nixon, and his political allies are well-versed in (and supportive of) that language and that time, we should all be afraid of the divisiveness that is to come. We should expect protests to continue, well past inauguration day. If people thought that Obama had opened up racial tensions, Trump’s appointments do not bode well for the future. I’d like to hope that Trump will indeed make things better – but, sadly, I’m not at all optimistic.